Commentary in The Drama Review (TDR): “Art in and for a Democracy”

It’s commonplace today to hear that democracy’s future is at risk. And as social media feeds us our daily diet of rancorous extremism, there is a growing recognition that culture is a central battleground for democracy’s survival. What is missing, and what we need, is a cultural strategy to fight back.

The authoritarian Right has long understood that culture is upstream from politics. In his bid for the presidential nomination at the 1992 Republican National Convention in Houston, Texas, Pat Buchanan put it this way:

My friends, this election is about more than who gets what. It is about who we are. It is about what we believe, and what we stand for as Americans. There is a religious war going on in the country. It is a cultural war, as critical to the kind of nation we shall be as was the Cold War itself, for this war is for the soul of America. (Buchanan 1992)

Buchanan’s declaration of the culture war was a direct challenge to the victories of the civil rights movement and all the other social justice movements that had sprung from it. There, too, culture played a central role. Beginning in the 1960s, artists across the US realized their communities shared the common plight of being exploited for profit by a relative few in powerful positions. They also recognized that prominent in the exploiter’s playbook was the plan to replace a community’s deep, distinctive histories and traditions with shallow, generic stereotypes. In Decolonizing the Mind, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o described this tactic as “the cultural bomb,” intended “to annihilate a people’s belief in their names, in their languages, in their environment, in their heritage of struggle, in their unity, in their capacities, and ultimately in themselves” (1986:28). Once communities stopped believing in themselves, they could easily be played off against one another in the time-tested winning strategy of divide and conquer.

Dudley Cocke

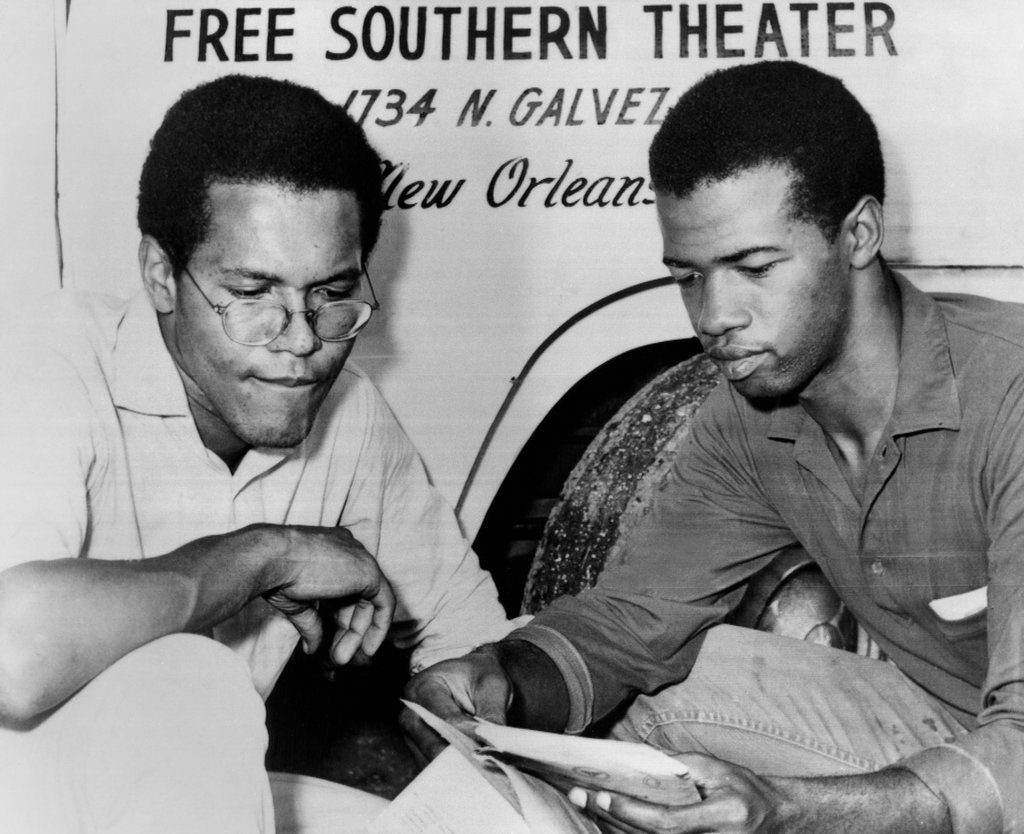

SNCC, The Free Southern Theater, Junebug Productions, & John O'Neal

John O’Neal, 1940-2019, helped build a theater movement that supported voting rights and crossed cultural frontiers. His work is part of a new book featuring the plays of Appalachia’s Roadside Theater. Roadside and O’Neal collaborated for decades on plays that built common ground across race and geography while honoring individual cultural identity. This is A.B. Spellman’s essay on that story, republished in the Daily Yonder.

A.B. Spellman, former deputy chairman, National Endowment for the Arts

Ron Short inducted into the Southwest Virginia Walk of Fame

BIG STONE GAP, Va. — The Southwest Virginia Walk of Fame will add 12 new members at the 15th Annual “Gathering in the Gap” Music Festival on May 27.

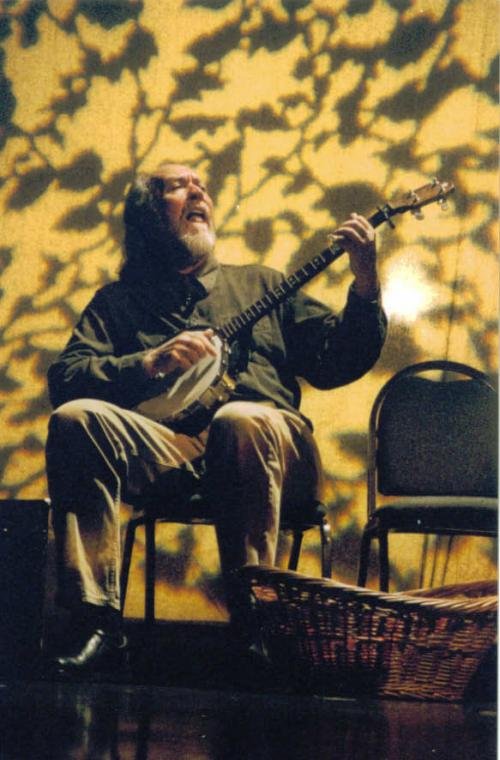

New inductees include Ron Short, musician, playwright, composer, and performer, from Dickenson County. For more than 35 years, he traveled locally, nationally and internationally with other members of Roadside Theater, telling the stories, performing in the plays and singing the songs of his Appalachian heritage, always with the goal of teaching others to value and share their own stories. His original plays and other work from Roadside Theater have been recently published in a two-volume collection entitled Art in a Democracy for which he also served as an editor. In April of 2023, Ron won the Tennessee Songwriters Competition out of over 1,000 entries. After residing in Big Stone Gap for 38 years, Ron now lives in Duffield, and enjoys playing in his band, Ron Short and the Possum Playboys.

David McGee

Broadway World: “Puerto Rican Theater Group and Appalachian Theater Group Collaborate at Bronx Event”

"We are thrilled to welcome Roadside back to New York for this special event," said Rosalba Rolón, artistic director of Pregones. "Local audiences have been captivated by stories and music of the people of Appalachia as crafted for the stage by the artists of Roadside. Their 50th Anniversary harbors three-plus decades of sustained friendship, creative exchange, and co-creation with Pregones! The coalfields and mountains of Kentucky might be worlds away from the streets of New York, but the heart and truthfulness of our artistry keeps us together."

By Stephi Wild

MIT Study: Reviving a Local Economy by Rebuilding Relationships: The Story of the Letcher County Culture Hub

This case study shares the story of the Letcher County Culture Hub, a multi-stakeholder initiative developed in a small Appalachian community that had been struggling with economic stagnation, unemployment, and drug addiction in the wake of the coal industry’s collapse in the region. This case study describes how the Culture Hub model was developed and shares it as an example of local innovation with lessons that can speak to challenges facing communities far beyond Appalachia.

Elizabeth Hoffecker, Research Scientist, Local Innovation Group Lead

Ben Fink and Arnaldo López speak at the School of Visual Arts in NYC

This event at the School of Visual Arts featured Art in a Democracy's editor Ben Fink, who spent many years in the Roadside Theater ensemble making theater and organizing in the Kentucky coalfields and with allies across the country, and Arnaldo Lopez, managing director of Pregones Theater in the South Bronx. Roadside and Pregones collaborated together for decades, producing plays like Betsy! and, together with Junebug Productions, Promise of a Love Song. Through sharing and discussing stories from Roadside and its collaborators, as well as from our own experience, they probed the legacies of American populism, the connections between art and politics at the grassroots level, and the possibilities of making a democratic way of life.

Ben Fink and Kate Fowler on Arlene Goldbard’s podcast talking about Art in a Democracy and Southern Arts and Culture Coalition

Roadside had a sustaining success by building relationship: spending time, collaborating deeply, bringing as much nourishment to the places they visited as to their own place. When they started, the typical audience survey of U.S. theaters revealed a largely white and prosperous audience, but as their way of working evolved, the figures for Roadside’s own performances portrayed an economically and racially diverse audience that suggested to the theater world what was possible. When the funds to sustain that approach were cut off, audience surveys snapped back to the bad old days. The question arises whether a new generation will able to use and develop that model under current economic and political conditions.

Arlene Goldbard on her interview with Kate Fowler and Ben Fink

On Cultural Organizing and Performing Our Future

Like conventional organizing, cultural organizing is about building power, understood as organized people plus organized money plus organized ideas. The difference is cultural organizers organize not around problems but around projects: music concerts that reflect the contributions our communities have made to world culture, plays that retell our communities’ stories in residents’ own words, community-run businesses that employ neighbors in recovery. These projects draw on and enhance a community’s shared material, its intellectual, emotional, and spiritual richness—its commonwealth. Artists, used to being treated as outside experts and gig-entrepreneurs, join this work as neighbors, with key skills to contribute. Government officials, used to steering the conversation, join this work as equals, no greater or lesser than anyone else. Youth, elders, poor folks, and others who are used to being ignored join this work as full participants, and are fully heard.

By Denise Griffin Johnson and Ben Fink

Change the Story / Change the World Podcast Episode: Art in a Democracy

This episode is Art in a Democracy: Selected Plays of Roadside Theater. Our conversation with editor Ben Fink and contributor Arnaldo J. Lopez. explores Roadside's 50-year history of creative collaboration percolating at the crossroads of art, community, and America's struggle to craft an authentic living democracy.

Bill Cleveland

Who's Afraid of Art in a Democracy?

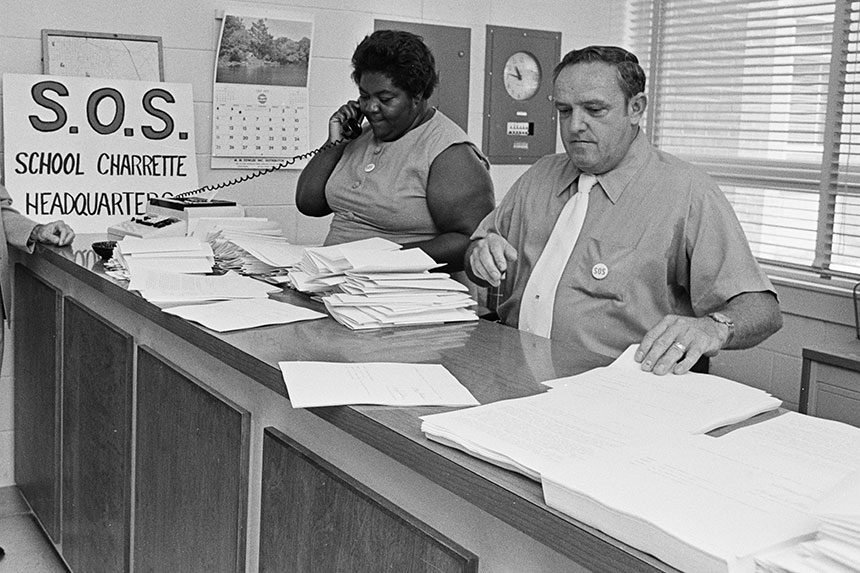

"In 1971, a janitor in North Carolina named C. P. Ellis was asked by his union to help lead a project about racism in the schools. Ellis, who at the time was president of the local Ku Klux Klan, was not expecting this invitation. Then the same union leader nominated local Black leader Ann Atwater to be Ellis’s co-chair. Ellis later told Studs Terkel he “hated” Atwater “with a purple passion.” But he took the position anyway. Mostly, he said, he did it out of “a sense of pride. . . .Here’s a chance for a low-income white man to be somethin’.” Atwater, of course, had every reason to walk away. But she didn’t. And so began the transformation of a Klansman into an anti-racist union organizer.”

How a conservative coal county built the biggest solar energy project in East Kentucky

Our work goes beyond making media. We work alongside partners from the Deep South to the South Bronx to turn our approach to storytelling into a new method of community-based cultural work, organizing, and wealth creation—what we call Community Cultural and Economic Development (CCED). Unlike standard approaches to development, CCED starts not with a community’s problems, but with its common values, traditions, and desires.

The solar energy project was born from this approach, demonstrating how CCED can leverage communities’ cultural strengths to address common challenges and seize new opportunities.

By Ben Fink, community organizer and series editor

Commentary: Community Organizations Work Best

In a Kentucky coalfield county that twice gave Trump 79% of its vote, volunteer fire chief Bill Meade is known as a particularly outspoken Trump supporter. When we invited him to meet with grassroots leaders at the oldest African American social organization in Baltimore, some people got nervous. But when Bill walked in the front door and saw the Narcan—the same medicine he and his fellow firefighters use to treat opioid overdoses back home—he knew he was on friendly ground. His hosts seemed to feel the same: after watching him perform in an original play about his neighbors’ struggle to survive the collapse of the coal industry, one of them commented: “We didn’t know white people had those problems, too.”

As we enter a dangerous moment in this nation’s political life, these are the kind of connections we need. We’ve been part of making them happen on a small scale in communities across the country. With the right investment, they could be happening everywhere.

By Dudley Cocke and Ben Fink

Ron Short Named Tennessee Songwriters Week Finalist at The Down Home in Johnson City

Bristol, Va.-Tenn. (Feb. 23, 2023) – The Birthplace of Country Music (BCM) and the Tennessee Department of Tourist Development are proud to announce singer-songwriter Ron Short has earned his place in the spotlight at Nashville’s famed Bluebird Cafe as the winner in the Tennessee Songwriters Week showcase round at The Down Home in Johnson City, Tenn. Wednesday night. Short was one of four songwriters out of 20 to advance from the qualifying round held at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum earlier this month where he performed his sentimental ballad entitled “France.” He competed against 17 other songwriters at The Down Home, each had advanced from qualifying rounds held in venues across Northeast Tennessee.

Ron Short is one of the editors of the series and was a key playwright, musician, and actor at Roadside Theater

Bound for Ameri’ky: Poetics of Inter-Racial Collaboration in the Puerto Rican-Appalachian Musical “Betsy!”

"In Betsy!, secrets function as a gravitational force that pulls towards the light threads of unspoken connections between generations of racialized immigrants. The normalized history of the United States inevitably includes stories of travel, settlement, and love in mixed company. The facts are generally accepted: the people who came before us, in some cases indigenous to the land and at other times by forced or voluntary arrivals, engaged in a struggle of belonging and displacement that endures to the present day. In Betsy!, however, that familiar story bends in a different direction. Betsy! reveals a powerful and often painful secret: the ancestors we claim do not always tell the whole story of who we are."